The last thing Dominick Hand would grab before running out of his dorm at UNC-Greensboro, even on a sprint across campus for snacks, was his book bag.

There was nothing in it he necessarily needed — not the criminology book often weighing it down or even a pen. But he thought the sight of him and his bag put others at ease — and might prevent him from being singled out by police.

Hand, who will graduate at the end of this semester with a double major — sociology with a concentration in criminology, and African American and African Diaspora Studies — wanted to send the message that he belongs on campus.

Some black instructors — work bags slung across shoulders or coursework in hands — have confided that they use the same strategy.

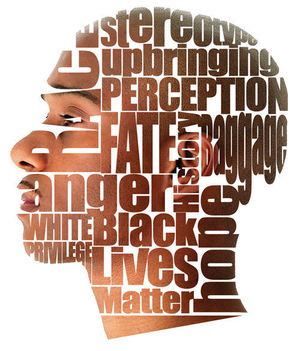

This concern is not unique to UNCG. In a variety of settings, young black men say they believe that not understanding how they are perceived in society can cost them a night in jail. Or their lives.

In the past two years, their fears involving race have played out almost daily in the news as Michael Brown, Trayvon Martin and Tamir Rice — young black men shot by police or under controversial circumstances — have become household names.

The problems facing young black men are too widespread and complicated to be explained in one night or a single article.

But many feel it’s a start to a conversation that needs to be had.

According to a number of studies, young black men are on the bottom rungs of almost every measure of success in this country.

In interviews with the News & Record, they describe feeling powerless, voiceless and disrespected.

They laugh to keep from crying. That has led to the birth of a number of Twitter hashtags, including #drivingwhileblack and the accompanying stories of being pulled over by the police.

“They are very much aware of the moments in which they are being treated differently,” said Tara Green, a professor and director of UNCG’s African American and African Diaspora Studies program.

Retired N.C. A&T sociology professor and administrator Bob Davis said he knows the studies and statistics on how, from employment opportunities to housing, race colors day-to-day experiences. As a radio host of “The Bottom Line,” an N.C. A&T public affairs call-in show, he often gets an earful from callers.

And he has lived it.

Davis recalls stopping at a convenience store late one night. As he pulled into a parking space, he could see the clerk behind the counter reach for a gun and tuck it under his jacket.

So Davis held up his money as he went through the door to show that he was interested in buying something.

“What if I had made an innocent — but sudden — move?” Davis asked.

If you are born black in America, he said, your reactions to situations probably are different from an average white person’s experiences.

These experiences based on race also help to explain why the majority of whites and the majority of blacks can look at the same set of facts and walk away with different interpretations.

“Young black men tell me there are times when they get stopped by the police and they know they didn’t do anything wrong,” said former Guilford County Chief District Court Judge Lawrence McSwain, who is black.

It has happened to him.

Years ago, he was traveling through Louisiana after a road trip to Brownsville, Texas, with his wife.

The speed limit was 55 mph, and he said he was driving between 55 and 60 mph.

And then he spotted the police lights in his rear-view mirror. As cars sped right past them.

A white police officer wanted to know whose car he was driving. He also asked McSwain for identification and requested that he get out of the car.

The officer went to his patrol car and came back.

“He said, ‘You can go, but I stopped you because you were going the speed limit,’ ” McSwain recalled.

No other explanation.

Someone from the area would tell him later that what he experienced often happened to other black men.

“I did feel humiliated … when I knew what I was doing was supposed to be right,” McSwain said.

The exchange had long-term effects for the legal-rights scholar.

“The end result is I’m supersensitive any time I see a law enforcement vehicle behind me,” McSwain said.

So it’s not farfetched that Steven Cureton, a black associate sociology professor at UNCG who took in his nephew, would sit him down and go over — as many black parents say they now do — things to do and not do when he is in a car with other young black men who come in contact with the police. It includes: direct eye contact with the officer and no sudden movements. Do not reach for identification until the officer says so. If it’s night, make sure the car’s inside light is on to give the officer an easy visual.

And never get into a car with more than three males, he told him.

“We’re not talking about what’s fair,” Cureton said. “We’re talking about people’s perceptions of what you have to do to survive.”

Race is a complicated issue.

People are afraid to talk about it out of fear of offending someone. It’s uncomfortable to discuss, which is part of the problem.

The concept of “white privilege” also means white people don’t have to think about it.

But it has far-reaching impact.

Race largely influences where people live, work, play, worship and socialize.

A Harvard Law School study showed how when two candidates with the exact same qualifications — “Greg” and “Jamal” — applied for the same job, the less ethnic-sounding applicant almost always got a call back.

It has been 50 years since the Greensboro sit-ins, which the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. said gave the civil rights movement a second wind for the fight for equal treatment.

“The reality is we haven’t gotten that far beyond that,” said Claude Barnes, a former political science professor at A&T and longtime advocate for social justice.

And when you look at, say, a map of where people live in the city and what their salaries are, the predominantly white areas are shaded by higher-income levels and the predominantly black areas are shaded by lower-income levels.

Barnes, a senior research associate at the Beloved Community Center in Greensboro, said it’s difficult to move forward when racism is institutionalized. The problems are both economical and cultural, he said.

The 1960s federal government report, “The Negro Family: The Case for National Action,” noted that “the Negro family, battered and harassed by discrimination, injustice, and uprooting, is in the deepest trouble.” The Atlantic magazine reported that as recently as the year 2000, more than 1 million black children had a father in jail or prison. Studies link that loss with behavioral problems and delinquency, especially among boys.

“We let society off the hook,” Barnes said. “We tend to suggest the problems black people face are … of their own doing.”

He points to school textbooks that essentially gloss over the magnitude of slavery, which has produced a legacy of outcomes for young black males, including unemployment and a high incarceration rate.

Bob Williams is a white man who teaches anti-racism courses. An economics professor at Guilford College, he went through the training 15 years ago, when elected head of the school’s faculty.

“One of the things that really is important (to the discussion) is this concept of implicit bias and implicit racial bias,” Williams said. “What that means to me is that I know that from an early age I was bombarded with a whole variety of messages.”

He said they came from family, friends, neighbors, church and TV about what other people were like.

“People of my age, we all grew up on TV Westerns and in all those Westerns, white people won and the Indians lost,” Williams said. “We all grew up on comic books, and all the superheroes were white, and the villains could be white or nonwhite.

“All of those formed images.”

That message, essentially, was that white people were to be respected until they proved themselves otherwise.

“We all have these messages, way deep in our subconscious that we are not even aware of,” Williams said. “But when we hit certain moments, they are what can really drive our behavior.”

Those moments have become more apparent thanks to social media and cellphone recordings. Things that some white people and some black people might have thought couldn’t possibly be true can be found on YouTube and Facebook.

In April, the nation collectively gasped while watching a white police officer in Charleston, S.C., shoot a black man he had stopped for a traffic violation eight times as the man ran away. A bystander recorded the incident.

In Greensboro, authorities eventually dropped the charges against two brothers who recorded what they said was an abusive an encounter with police.

“At some point there has to be — and I hate to say this because we say it so much — an honest conversation about black men,” said Cureton, the UNCG sociology professor.

Get a good education. Serve the country. Be good citizens.

The majority of black men are trying despite the obstacles.

“We are told to jump through all these hoops … and we still wake up and see all these outcomes,” Cureton said.

The Rev. Amos Quick, the longtime vice chairman of the Guilford County Board of Education, explains how it shows up in schools. Black children, for example, are not given the benefit of being children for a very long time, he said.

About 21 percent of Guilford students are black males, for example. But black males made up almost half of the reported discipline referrals in the 2014-15 school year, according to school system data.

“The research shows and data points out that even when students of different races do the exact same thing, the discipline is different and harsher on African Americans, particularly males,” Quick said.

He added that we must figure out the academic achievement gaps among black males, which cross income lines.

North Carolina’s overall grade level proficiency rate is lowest for black students, about 37 percent, compared with the rate for all students, about 57 percent. Black girls have traditionally scored higher than black boys.

Quick said society must acknowledge that the learning process is affected by the social, economic and historical realities outside the classroom.

“When we fail to educate African American males we are missing out on something,” he said. “We must acknowledge that there is a difference in the treatment of the children, we must agree that that’s not acceptable and then we must work together to change the outcome.”

Quick points to President Barack Obama and Dr. Ben Carson, a retired neurosurgeon vying for the Republican nomination for president.

“We shouldn’t point to their success and say we’ve arrived,” he said. “We should point at their success and say how many others are there who could be doing these things?”